By Lacy Wood

Global Roots

Everyone has an opinion about coffee. At Kalsada, we love to drink it, and we most certainly love to talk about it. If you buy your coffee in the grocery store, the label may tell you that your coffee is 100% Arabica or that it was bought from a farmer who is organic or fair-trade certified. However, these labels only give us a glimpse at the rich history behind each bean.

In the 1940s, the coffee-producing and -consuming countries got together to create a worldwide quota system, restricting the amount of coffee each producing country could sell. The International Coffee Agreement (ICA) limited the supply of coffee on the international market. By regulating the supply of coffee, the price of coffee was relatively stable for close to 50 years. This stability caused a slow climb in prices paid to producers, incentivizing the production of coffee as a cash crop.

By the 1980s, after 40 years of price stability and an entrenched belief that coffee was reliable as a source of profit, many countries in South America and Africa were wholly dependent on coffee for income. For example, in Burundi and Rwanda, prior to 1991, 80% of the money coming into the country for goods purchased was coming from coffee.

International roasters, such as Nestle, Proctor and Gamble, and Kraft, lobbied for the destruction of the quota system in order to deflate the price paid to producers, thereby lowering their cost of production and maximizing profits. In 1989, major coffee-consuming countries, led by the U.S., joined the efforts against the ICA

World Coffee Prices.

Upon the ICA’s demise, countries were no longer restricted to selling a certain amount of coffee. Looking for short-term gain, producing countries rushed to sell their coffee as soon as possible. In 1990, prices for coffee reached a historical low and remained there for the first half of the decade. Many scholars point to economic instability from the collapse of coffee prices as a major contributing factor to the genocides in Rwanda and Burundi in the early 90s.

Since the dismantling of the quota system, coffee prices have fluctuated drastically, making it a risky commodity that often sees little benefit for farmers. Interestingly, prices for consumers have remained relatively stable historically. Even after the decline in prices paid to farmers, consumers continued to pay the same amount to international roasters for coffee that now cost drastically less. The four largest international roasters–Nestle, Proctor and Gamble, Saralee, and Kraft–each earn approximately $1 billion per year, with an average profit margin on coffee sales of 26%.

Nestle is currently the largest single buyer of Filipino coffee, at 87% of all sales. Therefore there is no doubt this multinational organization has more than a little influence in the Filipino coffee industry.

The low amount paid for coffee per pound forces farmers to lower quality in an attempt to lower costs. This produces a downward spiral that promotes abuse of the land, abuse of impoverished farmers, and a destruction of communities.

The Philippines’ Coffee Roots

Coffee production in the Philippines stems from colonial Spanish rule, with the first trees planted at the end of the 18th century. For many years, the Philippines was one of the largest producers of coffee worldwide, however, rust disease destroyed the crop across Asia by the end of the 19th century, allowing South and Central America to take the lead in coffee production. Indonesia has since replanted and is currently the fourth-largest producer of coffee worldwide, but this has not happened in the Philippines.

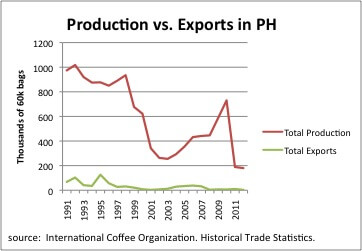

Although the Philippines has not been one of the major players in the global coffee industry in recent decades, this doesn’t mean that it hasn’t been affected by the demise of the ICA and subsequent price decreases. More and more farmers have been dropping out of the coffee industry, with production of coffee dropping sharply after the most recent drop in international prices in 2000.

We hope that our initial research phase will allow us to meet with farmers to hear their stories and pass them on to our international community.

Armed with a historical understanding of the coffee trade, at Kalsada, we are seeking to close the gap between consumers and farmers, use coffee to strengthen communities, and encourage the production of high quality, environmentally and socially sustainable coffee.